On the Risks of Distribution Inference

A blog post describing our work on Property Inference attacks.

Inference attacks seek to infer sensitive information about the training process of a revealed machine-learned model, most often about the training data.

Standard inference attacks (which we call “dataset inference attacks”) aim to learn something about a particular record that may have been in that training data. For example, in a membership inference attack

Differential Privacy provides a theoretical notion of privacy that maps well to membership inference attacks. However, it provides privacy at the dataset level. Thus, it doesn’t capture attacks that violate privacy at the distribution level. This is where property inference comes in. Property inference, a different kind of inference risk, involves an adversary that aims to infer some statistical property of the training distribution.

We illustrate the kind of risks introduced by property inference via a fictional example. Skynet, an (imaginary) organization that handles private data, releases a machine learning model

We picked this property as an example based on useful properties cited in the traffic classification literature (e.g.

Formalizing Property Inference

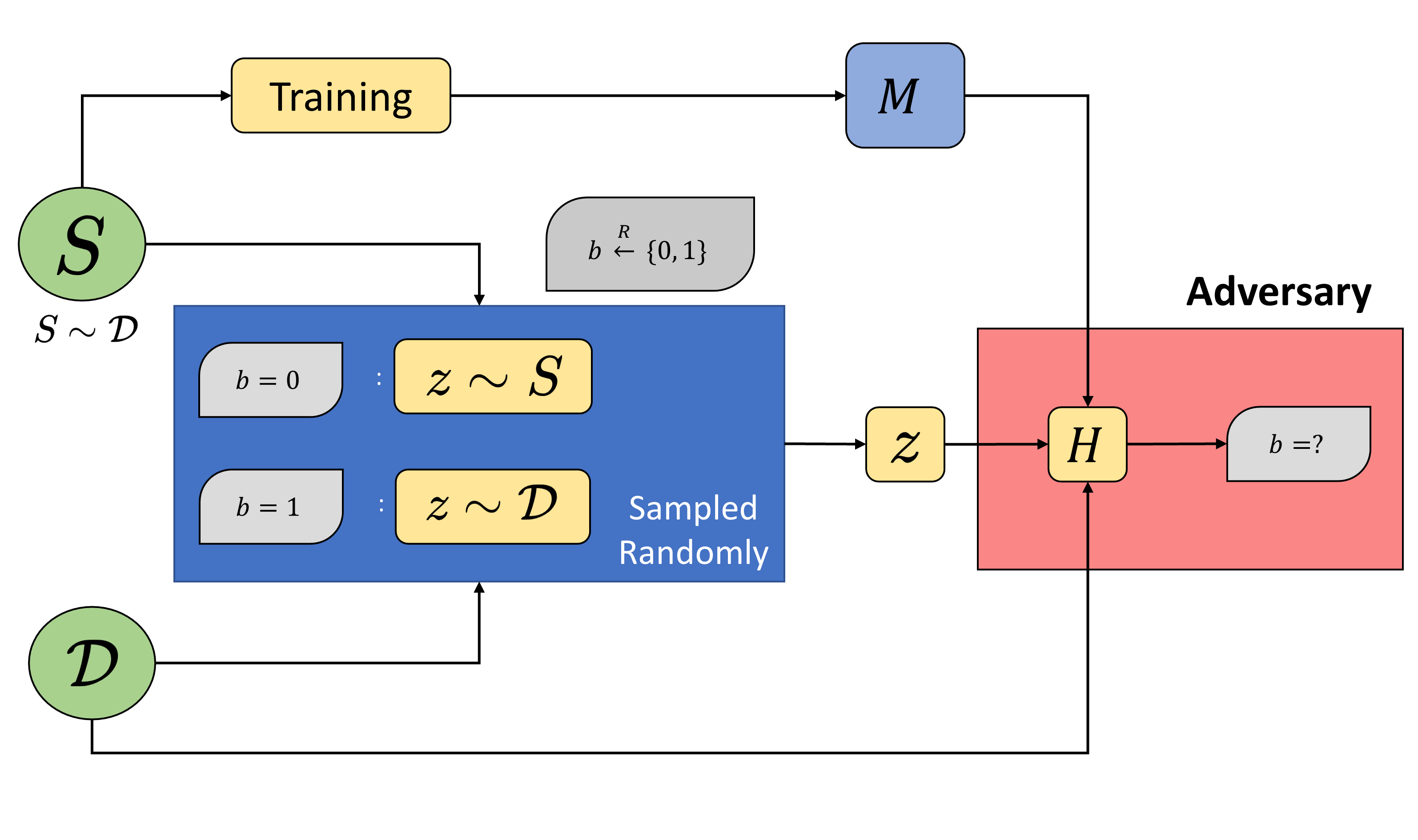

To formalize property inference attacks, we adapt the cryptographic game for membership inference proposed by Yeom et al.

In this game, the victim samples a dataset S from the distribution

In contrast, property inference focuses on properties of the underlying distribution ($\mathcal{D}$), not the dataset ($S$) itself. To capture property inference, we propose a similar cryptographic game. Instead of differentiating between the sources of a specific data point (

A model trainer

Given a model trained on this dataset $D$ drawn from either distribution

or , can an adversary infer from which of , the dataset was sampled?

Frameworks like Differential Privacy do not apply here: the adversary here cares about statistical properties of the distribution the model was trained on, not details about a particular sampled dataset.

Evaluating Risk of Property Inference

Most often in the literature, the adversary considers the ratio of members in a dataset satisfying a particular Boolean function

However, these experiments often test with arbitrary ratios, making it hard to understand the relative risk of different properties. Some examples are Chase et al.

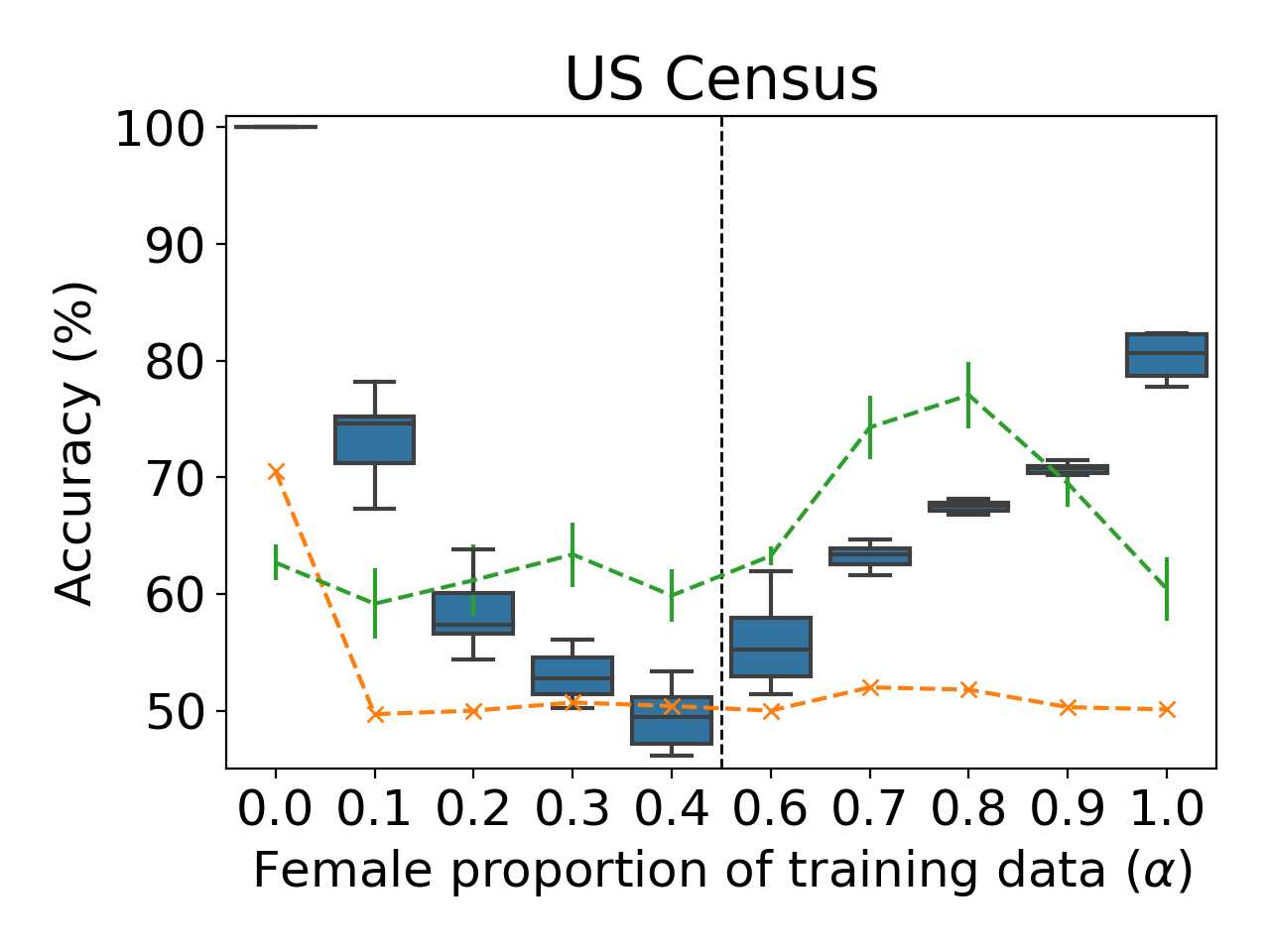

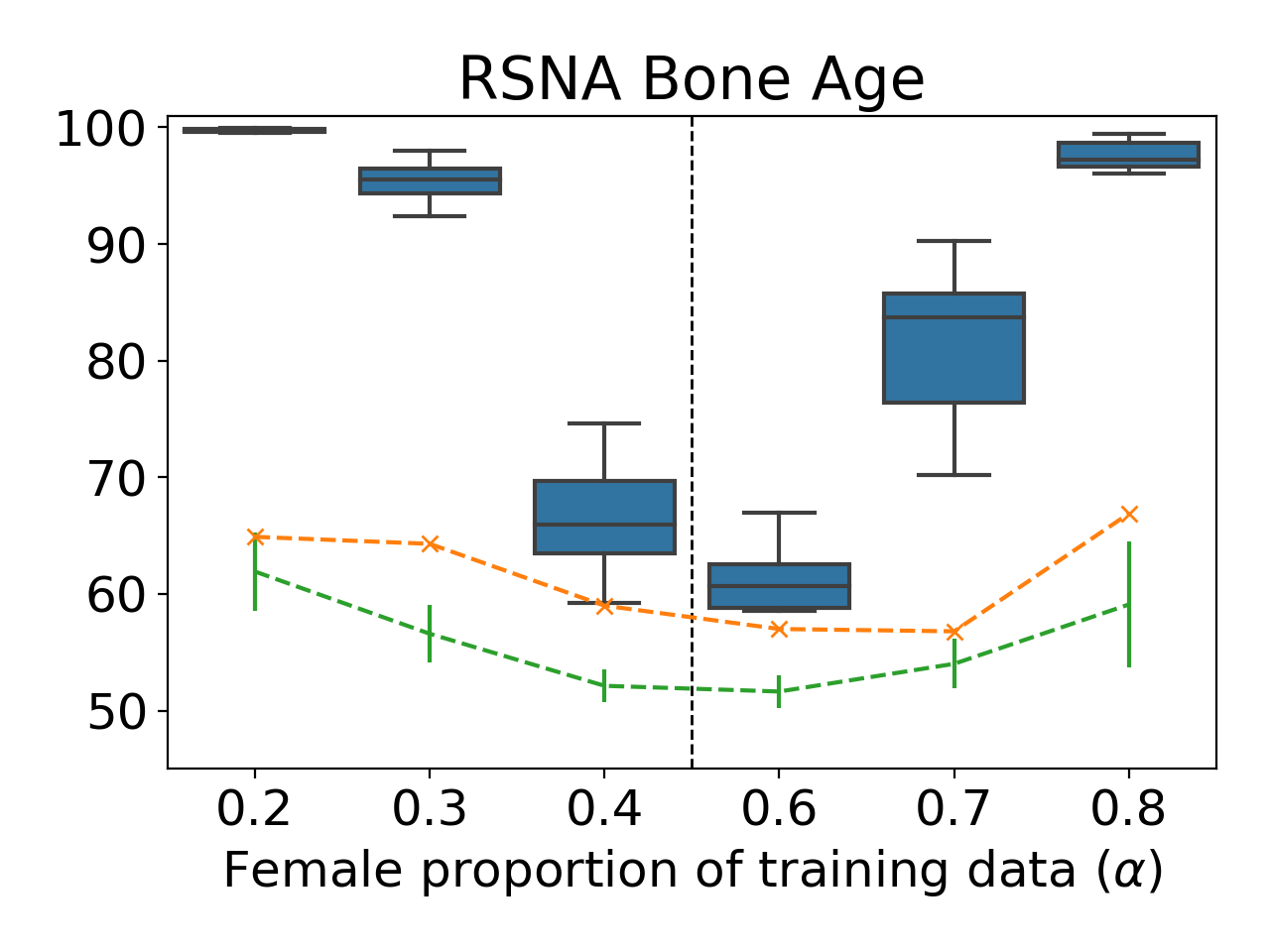

To better understand how well an intuitive notion of divergence in properties aligns with observed inference risk, we execute property inference attacks with increasing diverging properties. We fix one property (ratio=0.5) and vary the other ($\alpha$). We perform these experiments for three datasets: focusing on the ratio of females for the US Census and RSNA BoneAge datasets, and the average node-degree for the OGBN arXiv dataset.

The state-of-the-art method for property inference attacks involves meta-classifiers, usually using Permutation Invariant Networks (Ganju et al.,

We use two simple attacks (using only model outputs) as baselines:

- Loss Test: predict the property based on its performance on data from the same distribution it was trained, compared to the other distribution being analyzed.

- Threshold Test: extends the loss test by calibrating performance trends on a small set of models and arriving at a threshold based on model performance.

Experimental Results

Our results demonstrate how a meta-classifier can differentiate between models with ratios as similar as 0.5 and 0.6:

The meta-classifier attacks provide the best predictions, but the loss-test and threshold-test can serve as valuable baselines — even these simple attacks provide accuracies significantly better than random-guessing.

Inferring Graph Properties

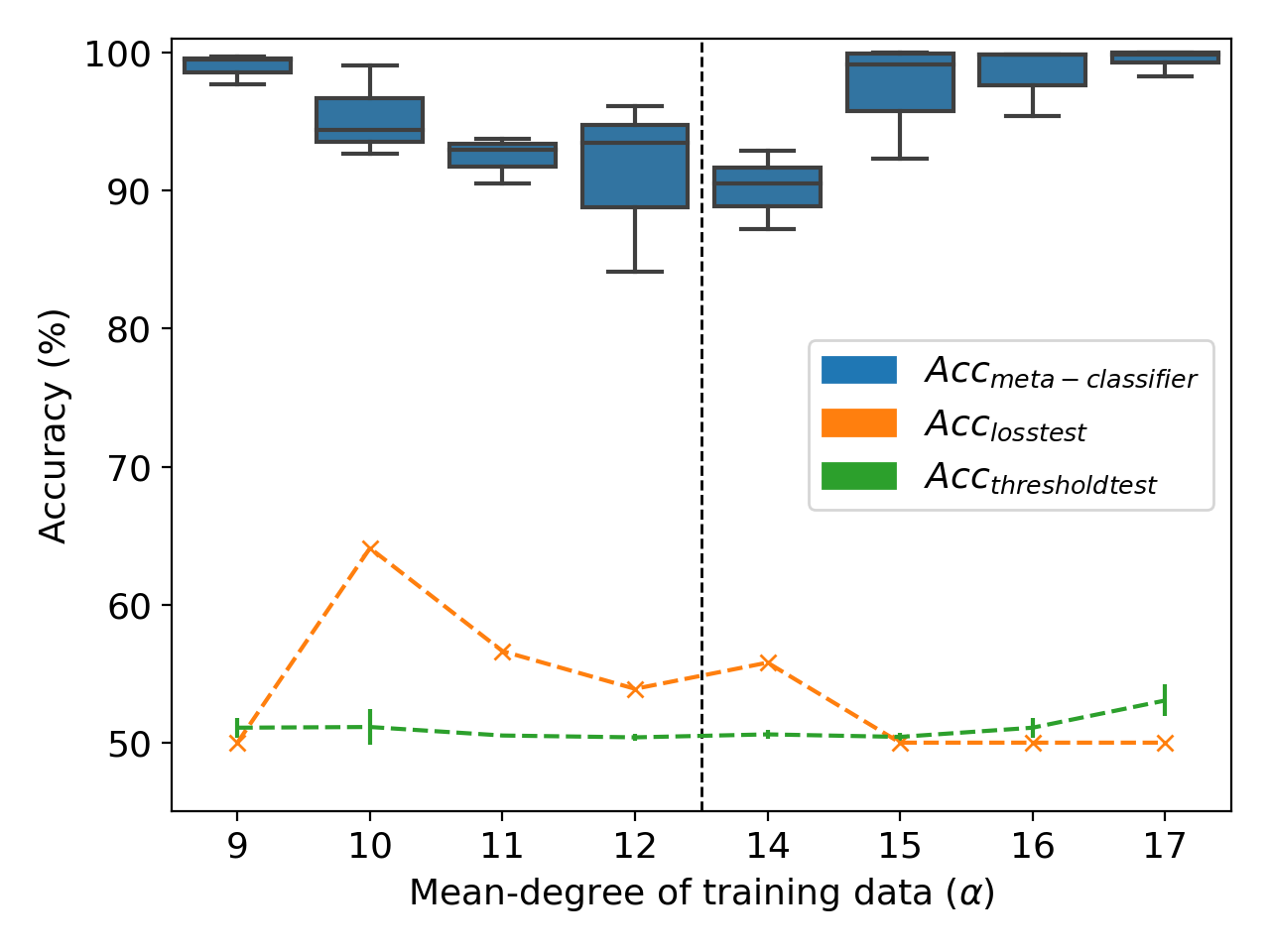

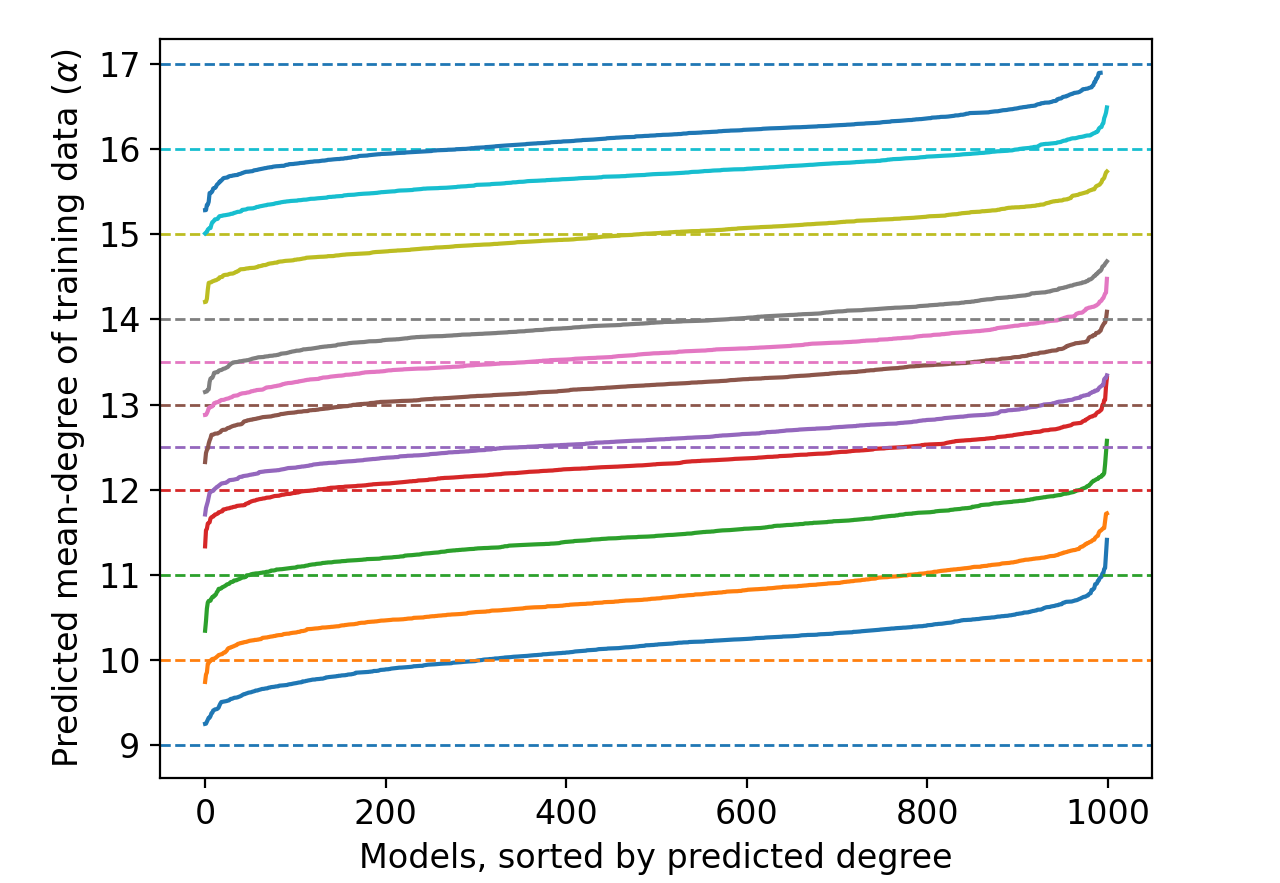

Our proposed definitions allow the property to hold over the whole dataset, not just aggregate statistics like mean ratio. Thus, we focus on node-classification for a graph: differentiating between versions of the graph with varying mean node-degrees as the property. We fix one property (mean node-degree 13) and vary the other ($\alpha$). Inferring the mean node-degree is a novel property inference task since the property here holds over the entirety of training data- no such property has been explored in the literature yet.

Our results demonstrate how a meta-classifier can also be trained to directly infer the mean-node degree of graphs (Figure 2). Encouraged by the success of meta-classifiers for this task, we also tried a meta-classifier variant to predict the mean-node degree of training graphs (Figure 3). The resulting meta-classifier even generalizes well, accurately predicting mean node-degrees for distributions ($\alpha$={12.5, 13.5}) that it hasn’t seen.

Summary

Our work on distribution inference formalizes and shows how property inference attacks can indeed infer distribution-level properties. Our ongoing work is focused on quantifying and studying this ‘privacy leakage’ of properties and its implications.

Anshuman Suri, David Evans. Formalizing Distribution Inference Risks - Workshop on Theory and Practice of Differential Privacy, ICML 2021.